Ludwig II, King of Bavaria from 1864 to 1886

Otto von Bismarck, Prime Minister of Prussia, First Chancellor of Germany

Bernhard von Gudden, “Psychiatrist”, Ludwig II’s Doctor

Luitpold, Prince Regent of Bavaria, Uncle of Ludwig II

Otto of Bavaria, Broher of Ludwig II

King of Prussia, First German Emperor

Surprise! This month we are changing things up a bit and hitting you with a double dose of history before diving into the mind and “madness” of Ludwig with Riley. Couldn’t leave you on the edge of your seat for too long after last week’s cliffhanger!

Clash of the Titans

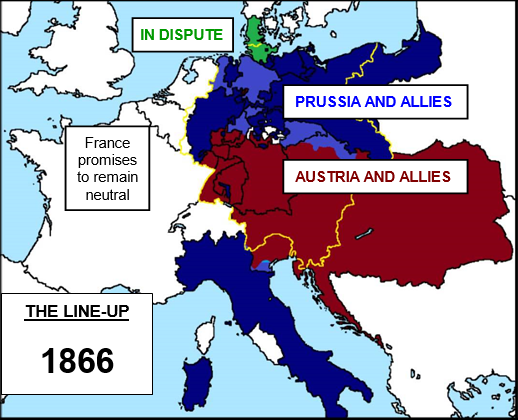

To understand why Ludwig II was removed from his throne and found dead within a week, we must first understand how he managed to royally piss off his government ministers and fellow noblemen. Ludwig was handed the crown during a difficult and contentious period of history in Europe. Clear leaders in terms of size and strength had emerged out of the German states by the second half of the 19th century. When Ludwig became king, Prussia and Austria were ranked one and two respectively. Ludwig’s Bavaria was in third, and inevitably this meant that if (and when) the big guns butted heads, they would be expecting Bavaria to choose a side. In 1866, this is exactly what happened. Otto von Bismarck was the prime minister of Prussia, and he had his sights set on a unified Germany with Prussia at the helm. Austria was not here for it. The fighters were entering their corners.

While Prussia was puffing its chest, ready to blow all the little pigs’ houses down, Bismarck was busy sweet-talking Ludwig into joining his team. Ludwig responded in the only reasonable manner as the sovereign of a country at the brink of being sucked into war – he ran and hid. The Bavarian king absolutely hated the idea of going to war against fellow Germans and so he did the most un-Swan Knight thing possible by avoiding his duty and leaving his government ministers to try to track him down at one of his many castles. Throughout his life Ludwig made a habit of distancing himself from Munich, the Bavarian capital, any time there was a conflict he wanted to avoid. But Ludwig’s advisors needed an answer ASAP, because Bismarck was pressing Bavaria hard to join him in the impending war against Austria. Ludwig’s disappearing act during this critical moment did not instill any confidence in him as a leader.

Eventually the decision was made for Ludwig when Prussia declared war on Bavaria. The sides were set – Prussia, Italy (don’t ask) and some smaller German states on one side and Austria, Bavaria and additional smaller German states on the other. Although the sides may seem about even on paper, the reality is that Prussia was a military powerhouse with state-of-the-art weapons. Because of Prussia’s decisive military advantage, the war was over in seven swift weeks, hence why it is also known as the Seven Weeks War. Prussia was the winner, and as a result they stood as the undisputed German heavyweight. The war ended with the Treaty of Prague on August 23, 1866, which kicked Austria out of what had been known as the German Federation. From this moment on Austria was its own entity, which is how we have the separate country of Austria today (New World Encyclopedia). Prussia was one step closer to unifying the rest of the German states. They were lenient with Bavaria considering that Ludwig’s country had taken up arms against them, but the Bavarian king’s mishandling of the situation did not win him any admirers.

It’s My Army I Can Cry If I Want To

Of course, once Prussia had a little taste of power, it was only a matter of time until it wanted more. Prime Minister Bismarck was highly ambitious, as was the Prussian King Wilhelm I. Although this is a story about Ludwig, in many ways, our Bavarian king was at the mercy of the history-altering decisions that Bismarck and Wilhelm made. Bavaria was not strong enough to challenge Prussia alone, and after the Seven Weeks’ War, they had signed a treaty with their German nemesis to team up for future conflicts. The future ended up not being that far off and within four years, Prussia was stepping into the ring with France. Once again, Ludwig fled. Although he eventually honored their agreement to fight alongside Prussia, he absolutely refused to participate as the head of the Bavarian army. This was an important duty of any king, if for nothing else than bolstering the troops’ morale. Again, this move did not win him any fans among his family and government ministers.

Prussia and its German allies were victorious, handing France a crushing defeat. The outcome of the Franco-Prussian War changed the landscape of Europe forever. Prussia’s King Wilhem was declared emperor (or kaiser) of Germany, and Bismarck became the “First Chancellor”. Ludwig’s power and influence as king of Bavaria was greatly diminished, and he refused to attend the celebration of Germany’s victory at Versailles in France. All around, it was not a good look.

Coup, There It Is

As Ludwig was losing prestige and the trust of his ministers as a result of his poor showing on the international stage, he was gaining one thing – massive amounts of debt as a result of his elaborate building projects. It’s true that what Ludwig did with his own money was his business, but the problem was that he didn’t keep it his business. Ludwig’s creditors began to pursue him, which threw the debacle into the public light and “the spectacle of a reigning monarch being sued in open court by his creditors exposed the royal family to scorn” (Greg King). Even worse for the Bavarian king were his rather unethical attempts to procure more money by pressuring his government ministers to magically come up with large sums, which “imperiled the continued operation of the state” (Greg King). Ludwig had managed to make enemies of his government through his lackluster performance of his royal duties, and now his embarrassing financial situation had turned his royal family members against him. The time had come to do something about their Neuschwanstein-sized problem.

In 1885, the 21st year of Ludwig II’s reign, his own uncle Prince Luitpold began to conspire with the Bavarian prime minister Johann von Lutz to remove the king from his throne. As Greg King explains, to remove Ludwig, Luitpold and von Lutz had to come up with an airtight explanation for their coup, or risk the king’s supporters rioting in the streets. As has often been the case in our stories, even though Ludwig had made enemies of his family and fellow nobles, he was still very popular with the common people. Peasants along the countryside were particularly fond of him, as he often visited his subjects during his midnight carriage rides through the woods. And so the men who gathered to betray Ludwig built their case around three elements: Ludwig’s risky financial habits, his horrendous record of performing his royal duties, and, critical to our story, his mental health. Yes Ludwig was strange and most definitely lived with his head in the clouds as he attempted to escape the dismal reality of the role he was born into. But mentally unstable to the point that he was unable to responsibly and coherently make decisions on behalf of his country? That was a stretch.

But this route was the one best suited to removing Ludwig permanently while avoiding pushback from his supporters. To accomplish this, Luitpold and von Lutz needed a doctor to make a diagnosis. That man was Dr. Bernhard von Gudden, a “psychiatrist” (I shudder to even attribute that word with this man) who was also the doctor of Ludwig’s troubled brother, Otto. There seems to be evidence that Otto did actually suffer from severe mental illness, which perhaps made it easier for Ludwig’s haters to attribute some of the same symptoms to the king. In today’s society of standards and protocols when diagnosing and treating mental illness (although far from perfect), it is astounding to learn how Ludwig went from king of Bavaria to prisoner in his own castle. Without EVER personally examining Ludwig, von Gudden delivered a diagnosis to Luitpold and von Lutz that “confirmed” the king was unfit to continue this royal duties. Under Bavarian law, the diagnosis made it legal to assign a regent (someone who ruled in the name of the king or queen in the event they were unable to). And who was the choice of the commission of traitors? Uncle Luitpold! What?? You mean he went through all that trouble just to put himself on the throne? Color me shocked.

Shudder Island

But Ludwig was not going down without a fight. In his later years, the king had lost the angelic good looks that had entranced both men and women when he was a young prince. He was now overweight and far from graceful, but he was still the king and he was competent enough to realize he was being set up. When the traitors cornered him at Neuschwanstein, Ludwig’s response to the charges showed that he was a reasonable and coherent man who was as confused by von Gudden’s diagnosis as I am 130 years later. According to records of the conversation between Ludwig and the doctor on the night of the king’s arrest, Ludwig dropped the following heat:

- “How can you certify me insane without seeing me and examining me beforehand?” FACTS (Greg King)

- “Listen, as an experienced neurologist, how can you be so devoid of scruple as to make out a certificate that is decisive for a human life? You have not seen me for the last twelve years!” MORE FACTS!! (Greg King)

The evidence of mental illness that the conspirators had collected included accusations that Ludwig often hallucinated or spoke to himself, was violent with his servants and often beat them, was eccentric, and had no control over his spending. Other than the money thing, it is hard to know if the other accusations were true, as there is evidence that many of the people who made the statements were paid to do so. But unfortunately for Ludwig, none of this mattered, as he was overpowered and physically removed from his beloved Neuschwanstein and imprisoned in another one of his residences, Castle Berg. Luitpold became regent with little pushback because of the nation-wide declaration of Ludwig’s incurable illness, and Ludwig was left to live his days under the watchful eyes of von Gudden and a team of orderlies. But for Ludwig and his doctor, there weren’t many more days left…

One of the concessions that von Gudden allowed Ludwig was to have escorted walks around the Castle Berg grounds twice a day. On the evening of June 13, 1886, von Gudden and Ludwig set out on one of these walks in the midst of a storm, and never returned. Both men were found dead that night, with Ludwig floating facedown in Lake Starnberg. What happened on that deadly walk will forever remain a mystery, as the only two people who were there to witness it died at the scene. Officially, Ludwig’s death was ruled a suicide by drowing, which doesn’t make sense to anyone with a basic IQ. Reportedly, the water where Ludwig was found was only a few feet deep and his lungs did not have any water in them, making it hard to believe that drowning was the cause of death. It is true that Ludwig had expressed suicidal thoughts from the moment he learned of his betrayal, but there were no signs of self-harm during the autopsy and I find it hard to believe that Ludwig killed von Gudden (the Bavarian government actually declared it a murder-suicide) and then somehow drowned himself in shallow water. Without swallowing any water…Much like the declaration of insanity that was placed on Ludwig without any examination, so too were rumors spread by unreliable sources concerning the condition of the bodies. The sad truth is that in addition to there being no reliable witnesses, any pertinent documentation that could shed some light on this mystery has long been lost.

One popular theory is that Ludwig’s beloved cousin and best friend Elizabeth (the sister of his former fiancée Sophie) had managed to plan for his escape and that was the reason the king insisted on taking a walk in the middle of the pouring rain. According to author Greg King, it is possible that he attempted to flee from his doctor, fighting him in the process (von Gudden has several cuts and bruises on his face), and drowned as a result of the weather, his excessive weight, and too many alcoholic beverages (Ludwig did drink an increasing amount of alcohol towards the end of his life). Other theories are that von Gudden tried to subdue Ludwig with chloroform, accidentally killed him and then had a heart attack as a result of the shock. Not buying it. Riley proposed the theory that Ludwig’s death was a hit to cover up the coup. It’s possible, but if that was the plan then it was a poor one. Ludwig’s removal from the throne and almost immediate untimely death made him a martyr in the eyes of many Bavarians, and it only increased his popularity.

Boulevard of Broken Dreams

With Ludwig II’s death, his brother Otto technically became the king. Of course, there was no way he was going to rule since he had been deemed insane long before Ludwig had. And so, Uncle Luitpold remained regent until his death in 1912 at the age of 92. When he died, his son took over the regency as Ludwig III and became king when Otto died four years later in 1916. But Ludwig III was only king for a brief moment – following the German Empire’s defeat in World War I, the monarchy was abolished and the royal Wittelsbach family was royal no more. As we know, the next few decades in German history were fueled by a hunger for power and a darkness that Ludwig II would have abhorred. It was perhaps for the best that he didn’t live to see what came next.

Ludwig II’s cousin Elizabeth perhaps said it best when she said, “The King was no madman, only an eccentric living in a world of dreams!” (Greg King). I think we can be pretty confident that Ludwig was not mentally ill to the point that he was unable to perform as king. Sure, he neglected his duties and definitely wasn’t the ideal guy for the job, but let’s face it, very few monarch were. Was he perfect? No. He made the decision to turn his back on his royal duties at the most critical times, preferring to live in a version of reality that brought him peace and comfort. How many of us can say we did not do something similar throughout the difficulties of this past year?

References

“Austro-Prussian War.” Austro-Prussian War – New World Encyclopedia, http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Austro-Prussian_War.

Katz, Jamie. “The Brilliant, Troubled Legacy of Richard Wagner.” Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Institution, 23 July 2013, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/the-brilliant-troubled-legacy-of-richard-wagner-16686821/.

King, Greg. The Mad King: the Life and Times of Ludwig II of Bavaria. Aurum Press, 1997.

“The Revolutions of 1848–49.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., http://www.britannica.com/place/Germany/The-revolutions-of-1848-49.

Taylor, Alan. “The 125th Anniversary of the Death of King Ludwig II.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 13 June 2011, http://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2011/06/the-125th-anniversary-of-the-death-of-king-ludwig-ii/100085/.

“Treaty of Frankfurt Am Main Ends Franco-Prussian War.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 5 Nov. 2009, http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/treaty-of-frankfurt-am-main-ends-franco-prussian-war.