Criminal Minds

In November 2017, Dr. Ann McKee presented images of a brain to a room of scientists and reporters. The brain was severely atrophied, or shrunken. The ventricles, which supply a cleaning fluid of sorts called cerebrospinal fluid, had expanded while the tissue had shriveled. At first glance, these images hardly seemed groundbreaking. This kind of brain damage is seen all the time in aged individuals. But this brain belonged to 27-year-old NFL player Aaron Hernandez, and was the most extensive case of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) that had been seen in a person his age. CTE, a degenerative disease caused by repeated head trauma, had been reported in football players before, but this was evidence that the disease developed much more quickly in these athletes than scientists originally thought. The case was further complicated by the fact that Hernandez died by suicide while in prison for murder. Could CTE, known to create dramatic mood and behavior changes, explain his violence?

Interestingly, many attempts have been made to explain the behavior of King Henry VIII, another man known for his violent rage. Taking into account his memory problems, lack of inhibition, personality change, obesity, and rumored sterility, proposed diagnoses have run the gamut from lead poisoning to Cushing’s disease. But in 2016, a group of neurologists from Yale put forth a new theory that was splashed across headlines: was Henry suffering from the effects of a traumatic brain injury (TBI)? And if so, much like Hernandez, could that in any way make him less culpable for the violence that he perpetrated?

Shaken Not Stirred

Normally, the brain is suspended inside the skull in that supportive cerebrospinal fluid I mentioned earlier. Imagine a very large olive floating in a martini. But when the head is struck or otherwise disturbed, the olive starts to bounce around, making contact with the glass. This sets into motion a series of immediate and long-term changes in response to the trauma. The impact often results in decreased blood flow, impaired metabolism, inflammation, and changes in neuronal signaling in the brain. These major disruptions can in turn set off a chain of molecular events that inadvertently cause more damage to the brain.

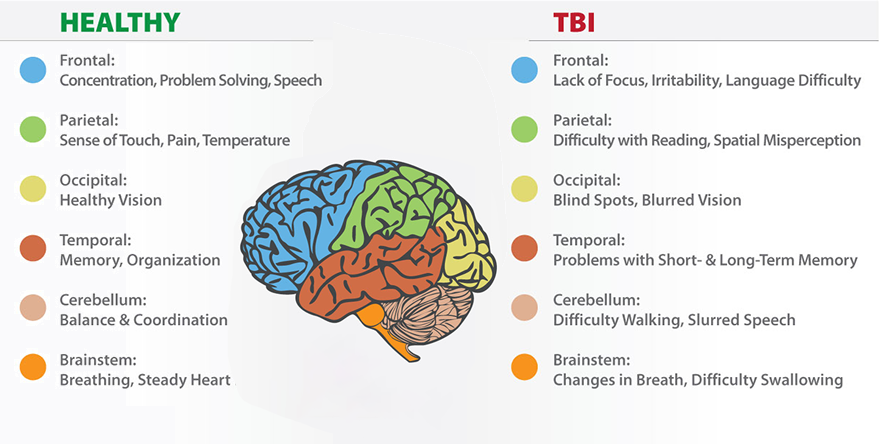

TBI, the acute response to a brain injury, is diagnosed clinically by symptoms such as loss of consciousness, confusion, and motor or sensory impairments. For all the former high school athletes who experienced a concussion, you may remember the trainer shining a light in your eyes or asking you to say the alphabet backwards (which I am unable to do when I am not concussed). TBIs can also cause more long-term neurological issues. Examples of these are CTE, which leads to degeneration of the brain, and Neurocognitive disorder, where the head injury interferes with your abilities like attention, memory, and language skills. In both of these diseases, symptoms linger after the initial peak injury period, and often include emotional and personality changes.

Get Off Your High Horse

The theory that Henry was suffering from the effects of traumatic brain injury aligns with historical evidence and scientific data. As Stefanie mentioned last week, Henry suffered at least 3 head injuries. The most significant occurred in 1536 while jousting, and historical sources suggest that he was unconscious for two hours, which does not bode well for the state of his brain. If you’re like me and the word “jousting” conjures up images of a cheesy Renaissance festival, know that this favorite royal pastime was no joke. Competitors were coming at each other on horses at top speed, aiming to knock one another off with solid wooden poles. The metal suits of armor that Henry wore weren’t exactly the most protective, and accounts of broken bones, impaled limbs, and fatalities abound. So even if Henry didn’t experience any other TBIs from jousting, the likelihood is high that he would have sustained many small disturbances that scientists call “sub-concussive blows” and believe can contribute to long-term cognitive impairments.

Henry’s subsequent mood swings, rage, memory problems, insomnia, and headaches, are all consistent with the chronic effects of TBI. Even more interesting, TBI could explain Henry’s impotence. Remember how Henry didn’t consummate his marriage with Anne of Cleves because he didn’t find her attractive? Some historians think there was more to the story. The ambassador to the Holy Roman Empire relayed rumors from Anne Boleyn that Henry, the notorious womanizer, “was not adept in the matter of coupling with a woman.” So, there are theories that despite Henry’s reputation, he may have been suffering from a lack of testosterone, known as hypogonadism.

One review estimates that 35% of TBI patients experience hormonal disruptions. If you remember last month’s story on Alexandra, the pituitary gland is the connection between the brain and the endocrine system. Head trauma can therefore alter sex hormone release, resulting in the delicate problem experienced by Henry. Moreover, the pituitary gland also releases growth hormone, and disruption to its signalling cascade may have contributed to Henry’s struggles with weight.

Head in the Game

We can say for sure that Henry suffered TBIs based on the accounts of his jousting and sporting accidents. What isn’t known is if the lasting effects to his cognitive abilities and personality reflect CTE, or a more mild Neurocognitive Disorder. Given that his symptoms seemed to emerge pretty quickly after the 1536 incident, I would venture to guess that he had Neurocognitive disorder, rather than CTE, which requires the buildup of underlying pathology over many years.

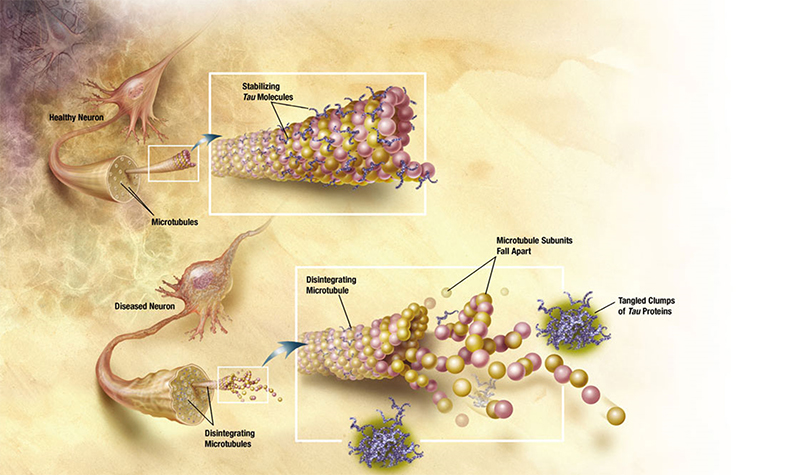

Dr. Bennett Omalu, who you may know as the character portrayed by Will Smith in the movie Concussion, first identified CTE in a football player in 2005. CTE is caused by repeated head injuries (i.e. domestic violence, professional sports, or military combat), and results in debilitating symptoms like aggression, motor difficulties, personality changes, depression, and dementia. Attempts to help people suffering from CTE are complicated by the fact that the disease can only be diagnosed by a post-mortem autopsy. Pathologists like Drs. McKee and Omalu look for clumps of protein called tau. Normally, tau provides structural support to your neurons, like a scaffold of sorts. But in diseases like CTE and Alzheimer’s disease, it misfolds and forms aggregates that impair the ability of your neurons to communicate, and can lead to cell death. Scientists are rapidly making progress on diagnostic strategies to identify patients while they are still alive and get them help.

Drs. McKee and Omalu are leaders in the CTE field, and their remarkable findings have been strongly opposed by the NFL, whose revenue is dependent on the brain rattling hits that cause TBI. From University of California and Boston University.

Sadly, that help often comes too late. As awareness of the prevalence and debilitating nature of CTE in football players has grown, NFL player suicide has also become more common. Between 1960 and 2007, nine NFL players (former or current) committed suicide, which was half the rate of suicide in men in the general population. But in 2012, six NFL players tragically committed suicide, and this does not include the high school and college athletes who have also taken their lives, grappling with mental health issues and fears of a future crippled by CTE. Because brain donations tend to be made by football players struggling with mental health and cognitive problems there is a bias in the brain samples available to researchers, and the scope of CTE in the sport remains unknown as a result.

Let’s Get Ethical

So we believe Henry and Hernandez were both suffering from debilitating neurological diseases associated with personality changes, including increased anger and aggression. There is no shortage of heartbreaking stories of families broken, careers ended, and lives ruined from the chronic effects of TBI. But the fact remains: Hernandez was convicted of murdering his friend, Odin Lloyd, and accused of killing two others. Henry sentenced many people, including his own wives and friends to violent deaths. Can a diagnosis make them less guilty?

Hernandez and Henry before their falls from grace. From US Magazine and Wikimedia.

I want to make clear here that violence of this nature is not the norm for TBI sufferers. While neurologists seem to agree that rage is one of the most universal symptoms of CTE, it’s something that the vast majority of people deal with without murdering someone. Therefore, I have reservations about using CTE as an excuse for Hernandez’s behavior. Undoubtedly, his brain exhibited advanced tau pathology. Given that he had been playing football since his youth, it is possible that he has sustained enough injuries to develop full-blown CTE before age 30. But it’s also possible to exhibit pathology without yet showing symptoms, so maybe his violence had nothing to do with brain trauma. In addition, the murder conviction wasn’t Hernandez’s first brush with the law. He was suspected in a double homicide in 2012, had several incidents related to domestic violence, and is accused of shooting a different friend in 2013. He also struggled with substance abuse, which could have amplified any aggressive tendencies he had.

Henry, too, was an angry man before his head injuries, and some of his most violent acts occurred before the infamous 1536 jousting accident. In 1535, he had his “‘intellectual courtier,’ secretary, and confidant”, Sir Thomas More, executed for refusing to take an oath recognizing Anne Boleyn as Henry’s true wife and queen (Marc’hadour). The same year, he started a campaign to punish 18 Carthusian monks who refused to acknowledge him as “Supreme Head of the Church of England.” These monks suffered gruesome deaths, ranging from starvation in horrific prison conditions, to disembowelment, to quartering.

After McKee released images of Hernandez’s brain, I saw many people switch in an instant from condemning him to defending him. Quickly, comparisons were drawn to another former NFL player who (let’s call it like it is) also committed murder, O.J. Simpson. Perhaps one day we will learn that he has CTE. But, will that change the way you feel about the murders of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman? Obviously, mental and neurological illnesses have the power to change people, and we should always have empathy for those suffering from them. However, to say that brain injury can fully explain and excuse the behavior of King Henry VIII or Aaron Hernandez is to say that we are nothing more than robots, executing the impulses from our brain without any input or control. And in my opinion, we are so much more than that.

Make sure to come back next week for an analysis of the historical implications of Henry’s TBI. Hernandez’s brain injury may have rocked New England, but the impacts of Henry’s reign were felt beyond England and across time.

References

Bellerby, R. (2018, May 9). Knight and Medieval Jousting. Retrieved from https://www.shorthistory.org/middle-ages/the-knight-and-medieval-jousting/

Carey, B. (2017, September 22). Yes, Aaron Hernandez Suffered Brain Injury. But That May Not Explain His Violence. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/22/health/aaron-hernandez-brain.html

Ikram, M. Q., Sajjad, F. H., & Salardini, A. (2016, February 5). The head that wears the crown: Henry VIII and traumatic brain injury. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0967586815006803

Iverson, G. L. (2015). Suicide and Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. doi: https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.neuropsych.15070172

Marc’hadour, G. P. (2020, April 27). Sir Thomas More. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Thomas-More-English-humanist-and-statesman/Career-as-kings-servant

Masel, B. E., & Urban, R. (2015). Chronic Endocrinopathies in Traumatic Brain Injury Disease. Journal of Neurotrauma, 32(23), 1902–1910. doi: 10.1089/neu.2014.3526

McKee, A., Abdolmohammadi, B., & Stein, T. D. (2018). The neuropathology of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology(Vol. 158, pp. 297–307).

O’Leary, R. A., & Nichol, A. D. (2018). Pathophysiology of severe traumatic brain injury. Journal of Neurological Sciences, 62(5), 542–548. doi: 0.23736/s0390-5616.18.04501-0

Ridgeway, C. (2015, June 9). Henry VIII and the Carthusian Monks. Retrieved from https://www.tudorsociety.com/henry-viii-and-the-carthusian-monks/

Rozek, R. (n.d.). Diagnosing Traumatic Brain Injury with the DSM-5. Retrieved from https://www.hg.org/legal-articles/diagnosing-traumatic-brain-injury-with-the-dsm-5-40990

3 thoughts on “Making a Murderer”